They Always Run: Inside RB Leipzig

Tom Curren heads inside one of the world's pre-eminent football factories

PRELUDE: STONE

In the early hours of December 4, 1943, a fleet of RAF heavy bombers took flight from airfields in the south of England. Between them they carried 1500 tons of incendiary and explosive bombs, all destined to fall on Berlin.

Except they weren’t. The RAF pulled a feint and, halfway to the German capital, changed course. The bombers reappeared ninety miles south-west, above the unblemished industrial city of Leipzig. The bay doors opened. Across the span of that long night, a city thus far spared the war’s violence was almost obliterated. The city centre, an old and storied symbol of east German history, was engulfed in a firestorm.

By the end of the Second World War, Leipzig was unrecognisable. Buoyed by the success of December 4, endless Allied attacks had reduced the city to 4.6 million cubic metres of rubble.

A decade after the bombing ceased, the rubble remained. The victorious Soviets put it to use. In 1956, Zentralstadion Leipzig was opened: a colossal venue in a huge open bowl, large enough to seat 120,000. It was built from the enormous weight of stone pulled from the ruin of Leipzig’s centre.

Today, 36 years after the fall of the Berlin wall, Zentralstadion is gone - almost. If you walk around the circumference of Red Bull’s gleaming, spaceship-style RB Arena, you’ll spot bits of weathered stone and old wooden seating dotted incongruously throughout the circular mound that is the new stadium’s cradle. Those are the remaining bones of Zentralstadion, and the last surviving ghosts of a city engulfed by fire.

Tom Curren is a writer living in London, and has been an Editor at SCOUTED since he founded it in 2014. He is interested in language and narrative journalism, and reports on the people of football, and the systems they exist under. He is not an analyst, he just works with a team much smarter than he is.

A voiceover booms. “This is our way,” it says. “Inspiring our audiences. Engaging them with our stories. Making them part of our journey of history in the making.”

Manuel Baum is, at the time of my visit in March, the Head of Youth Development at RB Leipzig. He’s introducing me to the club’s ethos by way of a presentation - right now, we’re in the midst of a sunny video on the merits of the Red Bull ‘world.’ “Growing together,” the voiceover continues, as F1 cars with iconic liveries zoom through the frame. “United in values and ambition. Pooling the sheer power of our network and the world of Red Bull. This is our way. In shaping the future of football - together.”

The future of football. I joke to members of the club’s staff that very few outfits have been featured as heavily on SCOUTED in the past decade as RB Leipzig. At this publication’s debut in 2014, scouting and recruitment was opaque and underreported. Data was still a dirty word in media circles and buying young players a practice relegated to the foolhardy and the Football Manager try-hards. RB Leipzig have played a significant role in turning that around. Joško Gvardiol, Christopher Nkunku, Dani Olmo, Dayot Upamecano, Tyler Adams, Ibrahima Konaté, Naby Keïta, Joshua Kimmich, Matheus Cunha; wherever you look in football, Leipzig have touched. Benjamin Šeško has finally joined Manchester United after months of speculation and Xavi Simons remains a wanted man; this summer has only continued the story.

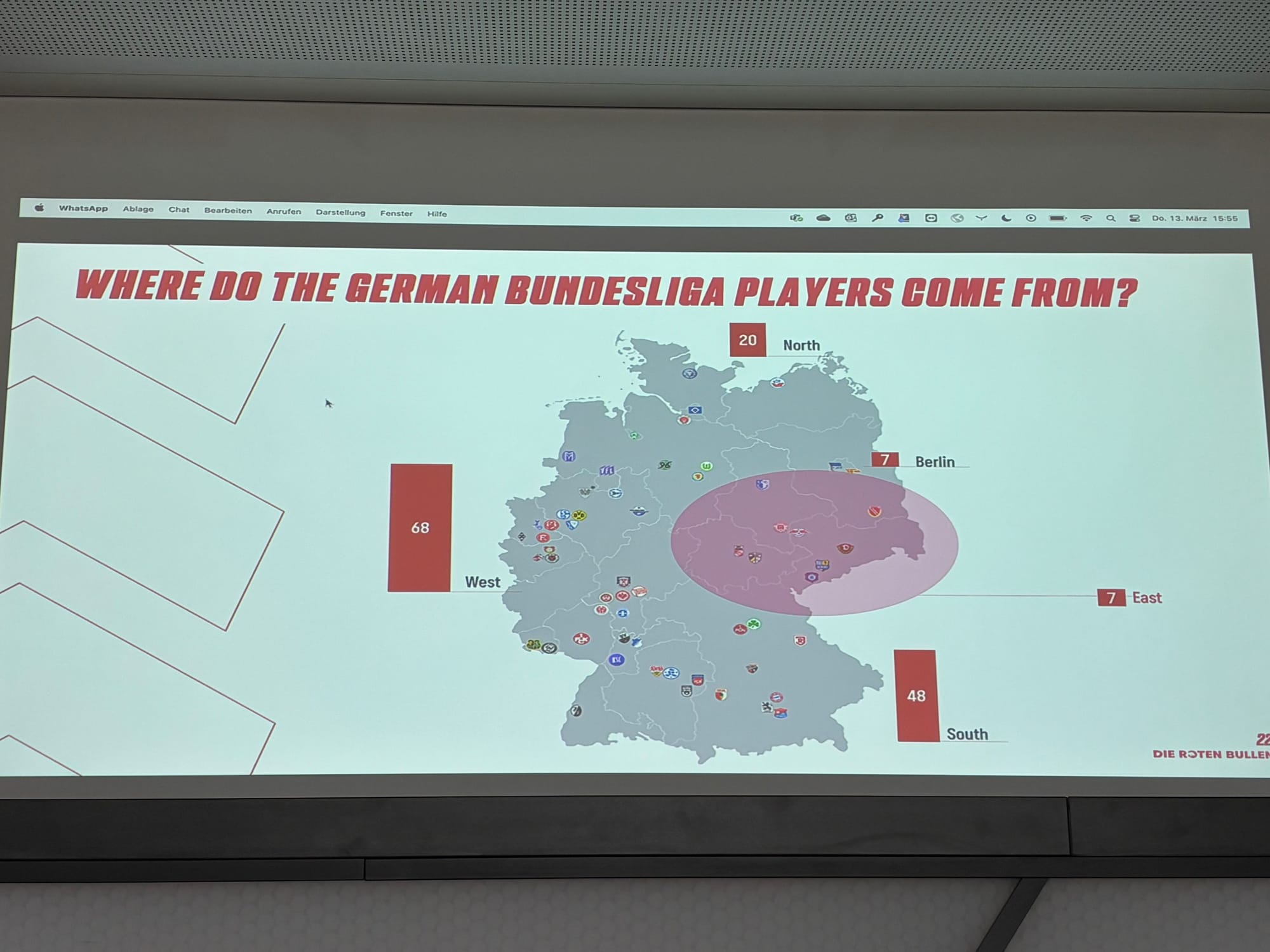

You’ll notice only one of the above names is German, and Joshua Kimmich was imported to Leipzig’s academy from Stuttgart, in the west. “If you look at a map of German clubs, they’re all concentrated in the west, north and south,” Baum tells me, pointing at said annotated map. “Between here and Berlin, there’s nothing. And we have a problem; around us there are no major footballing academies. Sometimes, when players join us, their previous level of footballing education is really low, because we don’t have enough good coaches around.”

The only other ‘major’ footballing power in former East Germany, other than RB Leipzig, lives unsurprisingly in the capital, and FC Union Berlin recently spent two years outside the top flight. Otherwise, a scattering of smaller clubs occupy the region, many of whom were founded during the Eastern Bloc. In many ways Leipzig are marooned. Today, employment and wages in the east still lag behind those of western Germany, a legacy of the centrally planned Soviet economy.

Baum clicks to the next slide, another map. “Most of the German Bundesliga players this season are produced in the west side [an annotation denotes 68 German players were produced in the west], south [48], north [20], Berlin [7] and east [7].” The annotations in the east side of the map are pointedly scarce. “We have to help the region. We have 600,000 inhabitants. It must be possible to develop a lot of players from this area.”

At this point, Baum is interrupted by a call from his mother, which he apologises for jovially. He's a warm guy, and a little sheepish about presenting in his excellent English. Before the academy job with Leipzig, Baum was a coach: first with SpVgg Underhaching in Bavaria, then with the youth teams of FC Augsburg and Die Mannschaft. He stepped up to an ill-fated first-team job with Schalke 04 in 2020, which lasted just ten winless games - although judging by that club's general disfunction, it's hard to hold him too accountable.

A few weeks before this story's intended publishing date, Baum left RB Leipzig. The departure was amiable; the club cited his 'personal reasons' for stepping down. He has been replaced by ex-Norwich City and Huddersfield Town manager David Wagner, a lifelong friend and collaborator of one Jürgen Klopp. Incredibly, Wagner was Baum's predecessor at Schalke, and himself oversaw a club-record winless run of 16 league games.

Anyway, in the present - which is the past, please keep up - Baum returns to his map. “We have to make out of the disadvantage and advantage - that’s what we’re thinking about at the moment,” he says. “I recently met representatives from AZ Alkmaar, a Dutch club. They focus only on developing players from their area, which has a much smaller population than East Germany. But they focus and set rules that they develop only players from their region - like Athletic [Athletic Club] or San Sebastian [Real Sociedad].

“The advantage is that the coaches there have to focus on those players. I think we should do similar, and really focus on our region.”

INTERLUDE: COLOURS

Below and to my left, a huge Pride tifo is unfurling from what was once the Zentralstadion: ‘diversity wins, in football and in life.’ Behind it, a boiling mass of red and white jumps up and down in RB Arena’s standing section; the stadium announcer conducts every wave of motion with a cry. Leipzig are welcoming Borussia Dortmund, whose players stream into the stadium like bees.

It’s perhaps a little strong to call RB Leipzig fans political refugees, but that’s not so far from the truth. Before Red Bull GmbH purchased the playing rights of fifth-tier SSV Markranstädt in 2009 and turned the resulting outfit into a Bundesliga mainstay, football fans in Leipzig were torn between two political forces.

On the left, the city houses BSG Chemie Leipzig. Chemie self-describe as progressive, and most would denote them simply as leftist; their charter explicitly states the goal of developing a club in opposition to ‘racist, discriminatory, sexist, and homophobic attitudes and intentions.’ Chemie’s ‘Diablos’ Ultras wear a deep green, attend anti-fascist demonstrations, and sing ‘All Cops are Bastards’ at home games. In 2019, they clashed violently with fans of FC Carl Zeiss Jana, another east German club.

On the right, Leipzig is home to FC Lokomotiv Leipzig, known locally as Lok. Although it would be unfair to call the club holistically right-wing, they are infamous in Germany for the fascist associations of their Ultra group. They wear yellow-and-blue, posted images of Anne Frank wearing the colours of Chemie, and in 2018 sacked two coaches after they were caught taking a photo of youth players performing a Nazi salute.

Both clubs have long, fascinating histories, the stories of which weave from the ripples of the Second World War, through the Eastern Bloc and reunification, to bankruptcy and renewals. Their derby lays claim to the largest attendance ever recorded in Germany: 100,000, at the Zentralstadion in 1956. But to make a long story unjustly simple, the clubs reflect the two halves of a city cut right down the middle by the political equator.

The rise of Alternative for Germany has been most stark in the country’s east. The 2025 federal election saw a staggering divide: look at a map of the country’s political districts and you’ll see a country split down the middle between the grey centre-right constituencies of the CDU in the west, and the bright blue of the AfD in the east. There are two islands of exception to the AfD’s eastern dominance: Berlin and, just south, marooned again, Leipzig.

Leipzig is bisected, too. The northern constituency, Leipzig I, was taken in 2025 by AfD; the southern, Leipzig II, by Die Linke, Germany’s leftist offering.

Amidst a city split in half stands the world’s largest producer of energy drinks.

Long-form writing. Proper research. No AI. No clickbait.

Find out moreThe project to turn a barren east Germany into a powerhouse footballing factory will be long and arduous. What RB Leipzig can focus on right now is what happens to players when they reach the club, whether from local sources or afar. This is where most of Baum's efforts went, during his two years at the club - and was his current focus, when we spoke in March.

“When I first joined the academy, I wanted to set out a mission,” he says. “What is our goal? ‘To develop professional footballers in a high-performance culture’. ‘Professional footballers’ here means not just for our first-team, because we have no U-21 side, and so the gap between the first-team and our academy is really high. It’s also a success for us when we have graduates in other Bundesliga clubs.

“When I arrived and collected information from the academy, I aligned every element with this mission. The challenge was they already had their own missions. For example, the physiotherapists were more ‘hospital’ physios than football physios. The athletic guys wanted to have the biggest muscles, but that’s not football related. The head coaches had a special playing philosophy and they only looked to the team, not the players. That’s only changed in the last half year. This year, for example, we had some of the youngest Bundesliga debuts in history. It’s a problem we don’t have an U-21 team, but it allows us to throw players in early.”

Those debutants were Viggo Gebel (2007) and Faik Sakar (2008); notably, both German talents raised at Leipzig’s academy. Later, as we walk through the club’s compound, a number of their teenage peers stroll the halls.

TV screens dotted around the training complex rotate through a selection of slides and curated videos: players of the month, notable goals and results, with every youth team offered the same space and time as the seniors. Through a door by one such screen is a long, intimidating red hallway that leads to the training pitches. It’s lined on both sides by a corrugated mural depicting a stampede of bulls that elongate and fill your vision as you walk. “The bulls always run against you,” a member of staff tells me with a grin.

“We have amazing facilities and resources,” Baum says. “Sometimes too much, because we want the players to work for stuff and not receive everything for free.”

The club are in the middle of several expansion projects, too. A gigantic headquarters is in the early stages of production nearby, and new pitches are being constructed for the U-19 teams.

We walk against the stampede and out onto the pitches, which are as pristine as you’d expect. When you turn and face the compound, RB Arena looms out of the grey sky above. The young players train and toil in its shadow. The summit of the mountain they’re climbing is an ever-visible reminder.

Something Baum says about youth football surprises me. When trying to pull the disparate elements of Leipzig’s academy together, he used a series of slogans to change the focus of coaches. “Youth football is an individual sport,” he stresses. “The team is only relevant in creating a learning environment for the expectations of the first team. We tell the coaches: teams don’t learn, individuals within the team learn. And teams don’t make debuts, individuals do.”

Back inside, the training complex opens up like the lair of a Bond villain, all hard angles in whites and greys. A large gymnasium hall is sunken into the floor; above, two glass-walled gyms face each other across its expanse. One is for the youth teams and another the seniors, designed so the kids can watch the first team as they train. Leipzig want as much cultural bleed-through as possible without bringing the two into constant direct contact. There is no separate building for the senior team; it all happens under the same roof.

Under that roof, the club’s pursuit of control is astonishing. Tracking data is generated live via cameras placed around the training pitches for analysts to review. Leipzig use this to monitor and control the output of their athletes in real time. Regular blood tests are taken to understand a player’s workload and remaining physical capacity, and the data is then used to limit their output in training. For example, they could know a senior forward has the capacity to safely make five high-intensity actions in a particular session; once the tracking data confirms he has, he’s done for the day.

Of course, most of a player's life is not spent at the compound - the club have an answer for that, too. They’ve developed an app to communicate with the athletes when they’re at home. Players are posed questions about their sleep, diet, and general wellbeing, and the club uses the answers to tweak their schedules. Video scouts and analysts can use the app to send players videos of their performances and walk them through mistakes - the players can respond with comments, a bit like a private social media network. Sleep rings are used to monitor the players when they’re in bed, and concerns in sleeping patterns are flagged and sent to labs for review.

“The facilities are amazing,” Leipzig newcomer Ridle Baku tells me, who was signed last summer. “It's really massive when I compare it with Wolfsburg and Mainz, where I played before. I don't know where it’s better than in Leipzig."

It’s no surprise Leipzig put so much emphasis on protecting the physical output of their players. If you know anything about the team on the pitch, you know they press hard and run with a ferocious intensity. “That’s our DNA,” grins Baku.

The bulls always run against you.

INTERLUDE: PEOPLE

In 1994, in a city newly freed from Eastern Bloc governance, the crumbling Zentralstadion was closed. Public access had been banned since 1990 due to concerns around riots amongst a public gripped by the fervour of freedom, and rising maintenance costs rang the death knell. A year later, foundations were laid for something new. It would be modern, safe, and built within the old stadium’s foundations; its walls would overlay the old running track exactly, and end where the stands once began. It was cocooned by the old stadium’s rise, held by it on all sides. Construction was completed in 2004, and two years later the new Zentralstadion hosted five games at Germany’s World Cup.

In 2009, Rasenballsport Leipzig was born, named so because German regulators do not allow clubs to be named after their ownership groups. There are no such rules for stadiums, and Red Bull GmbH immediately pursued the naming rights to Zentralstadion. They claimed them in 2010, when the club was still in the depths of the German league system. Zentralstadion was scrubbed from the record; the Red Bull Arena came to be.

Leipzig were promoted twice in succession and rocketed towards the Bundesliga in their new home. Fans arrowed towards it just as fast. Here, amidst the chaos and hooliganism of the city’s political divide, was a place clean of it. A place for families, for those who wanted to enjoy football in peace, away from the messy noise of real life. In 2016, the year Leipzig reached the top flight, a top-tier membership cost €1000 and did not include voting rights.

That same year, a severed bull’s head was thrown onto the pitch in a cup game against Dynamo Dresden. To say Leipzig were unpopular among German fans is to say a dog is unpopular in a cattery - or, to stretch the metaphor, a matador in a bull ring.

Germany’s ‘50+1’ rule is designed to ensure the majority of voting rights at clubs remain in the hands of its member association, and private investment cannot buy control - in theory, leaving power with the fans. For example, as of 2024, Borussia Dortmund had 218,000 members. But a loophole exists, engineered by Hannover 96 president Martin Kind: private bodies who continuously provide significant investment to a club for a period of twenty years or more can claim total control. When Kind reached that milestone in 2017, he did so. Bayer Leverkusen (Bayer), and VfL Wolfsburg (Volkswagen) are also majority owned by private bodies. In 2023, Hoffenheim majority owner Dietmar Hopp transferred his voting rights back to the members.

RB Leipzig do not qualify under Kind’s loophole, so must adhere to 50+1. And they do. Their membership association totals 17 members and it is still impossible to buy a voting share.

The year Leipzig reached the Bundesliga and the bull’s head splattered blood across the turf, the 17 members voted to purchase RB Arena outright. As of 2024, the capacity has been expanded to 47,069 seated and standing, which the club regularly fill. To reach the stadium, fans can enter through the original Zentralstadion’s atrium, and pass beneath a cathedral of the old city’s bomb-bleached bones. The stone watches them, silent as only stone can be.

“When you watch an RB Leipzig game, you can differentiate us from other clubs by four things,” Baum says, as he scrolls to a new slide. “Ball, game, body and mind. Ball is technicality; game is the playing philosophy; body is the athletic component; mind is personality. We educate our players with mastery programs, one for each of these pillars, and have a clear structure for how we train them.”

Baum is about to launch into a fascinating spiel on how Leipzig systematically improve some of the best football players in the world. Before we get to that, it’s important to set the foundations.

Baum is obsessed with culture, which might sound familiar. But unlike with managers who seem to impose their values across billion-dollar operations through sheer force of personality, Leipzig rotate around another kind of gravity: that of an Austrian multinational conglomerate.

“I want to be guided by Red Bull’s values,” Baum says. “Not rules. There are three core values Red Bull stand for. Meaning, which is to contribute and add value to something or someone. Freedom and responsibility, to have the freedom to work on something the way you want to. You need freedom within a framework: on the pitch, the lines are the framework. You can’t change the position of the goal, but you can change how you reach it. And mastery: to develop your strength and become excellent at what you do.”

Of course, the Red Bull ‘world’, as it’s routinely known, is still home to strong personalities; they just seem to act as stewards for company values, rather than imposing their own. As we speak, Jürgen Klopp is flying between clubs in the Red Bull network with his assistant, Peter Krawietz. They are both deep in Red Bull’s one-year onboarding process. When Marco Rose is sacked at the end of March, Krawietz will be parachuted in to assist interim manager Zsolt Löw, himself a long-term Red Bull coach who worked with Thomas Tuchel and Ralf Rangnick. In June, Werder Bremen's Ole Werner was announced as the club's new long-term appointment. And, as discussed, Baum has since been replaced with David Wagner, another Klopp stalwart.

How Klopp’s famous vivacity will dovetail with Red Bull’s values as he undertakes his role as Head of Global Soccer remains to be seen. Already, his fingerprints are everywhere, from Krawietz to Wagner and beyond. But we know his work will accentuate Red Bull’s existing ethos, not replace it. Meaning, freedom, mastery; ball, game, body, mind.

“When you watch RB Leipzig,” Baum says, “You can see our intensity. We want to press high, jump into duels, transition fast, and communicate very early. When Benjamin Šeško gets the ball, he needs to know exactly what David Raum is doing. Raum needn’t look at Šeško because he knows immediately he’s running to the far post. This is identity: there must be a red line from the academy to the first-team.”

Baum’s presentation here becomes very detail-oriented and, without the accompanying slides, somewhat challenging to translate to prose. But it was such a fascinating look inside the way Red Bull see football that it’s worth the attempt. Stay with me.

“When you make a decision as a football player, you use five signals,” Baum says. “Three of them are dynamic; one of them is the ball, because the ball is always moving. Then your teammates are moving, and your opponents are moving. If you make a decision - it doesn’t matter if you pass, shoot, or run - you use those three dynamics. Then you have two static signals: the playing direction, and the lines. These are the things you are communicating with the whole time, and they influence your decisions.

“We don’t want to develop a new philosophy the players have to learn. It must be intuitive. We’re trying to bring a player’s intuition alive.

“We develop most of the players in our academy not for the moment, but for the future. What does the future of football look like? A lot of clubs are really good technically. But what we’ve figured out, what we’re outstanding at, is developing KPIs. For example: how can you measure a 1v1?

“We take positional data out of every match, all the way through the club. Twenty-five times a second we get data from the players and the ball - and when you can write good algorithms you can measure these 1v1 situations.

“We have a definition that you and your opponent have to be in a circle of about two metres, with a line drawn behind the defender. And if you and the ball - or just you, in an off-ball situation - pass the line, which is related to the centre of the goal, you’ve won the 1v1.”

He plays a video of three examples: a player winning a 1v1 by passing through it; then winning a direct duel; and finally, of Šeško blasting a trademark rocket past his marker, via which the ball definitely passes the two-metre line.

“We use this for scouting, for quality information on the games and our players,” Baum finishes. “This is shared with the Red Bull soccer cosmos. We’ve made big steps in the AI and data world.”

INTERLUDE: WORLD

The bulls always run against you, whether you’re at an airport, watching motor racing, reading transfer news, on social media, or at your local corner shop; the bulls always run against you, everywhere, all the time. The iconic red-and-yellow livery is ubiquitous and inescapable. Two weeks after I return from Leipzig, an enormous 'gives you wiiiiiiings' billboard is plastered down my road.

This is the ‘world’ of which Rasenballsport Leipzig is but, in the grand scheme, a small part. In 2023, the planet’s largest energy drink brand sold 12.7 billion cans. As a privately held body it's difficult to get a proper handle on the company's value, but GmbH revenues for the 2024 fiscal year topped $11billion, and some estimations place its total market value at more than $50billion. RB Leipzig’s revenues reached a reported €450m in 2023 - astonishing for such a new outfit, but still just a drop in the caffeinated bucket.

Of course, Red Bull GmbH didn’t get into sports to make money directly. I don’t know how you’d calculate the brand capital generated by the extreme sports, Formula 1 teams, and young, powerful sport franchises Red Bull have sponsored or purchased, but I’m sure somewhere in a sprawling industrial complex in Austria there exists a very, very large number.

That all these sporting elements are aligned to Red Bull’s brand ethos is a marketing miracle and possibly one of the greatest commercial successes of the 21st century. It is an identity so strong it permeates billions and billions of dollars of investment and systems and management structures across a collection of fundamentally different verticals; in football, when a team announces its involvement with Red Bull, you know the shape of what they’ll become. The bulls always, always, always run against you, through the glass of the vending machine the same as they do the football pitch, and they don’t stop.

All this has been organised through one of football's most controversial contemporary developments: the multi-club model, of which Red Bull can be considered a progenitor. Currently, Red Bull own majority stakes in FC Red Bull Salzburg and FC Liefering (Austria), RB Leipzig (Germany), New York Red Bulls (U.S.), Red Bull Bragantino (Brazil) and RB Omiya Ardija (Japan) - the last of which was purchased as recently as November 2024. They also hold minority stakes in Leeds United (England) and Paris F.C. (France).

All this now falls under the purview of Jürgen Klopp.

The merits and implications of this model are well documented elsewhere. I'm simply here to recount the dislocating strangeness of being at the club and knowing it existed as both a distinct, singular entity, and a piece in an international puzzle. Red Bull's network loomed over Leipzig as the stadium looms over the training complex. It feels both distinctly German and transplanted. This is not, necessarily, a unique criticism; I struggle to think of any major footballing power that is not grappling with similar liminality, although Red Bull have certainly taken it further than most.

I think of Baum's comments about Real Sociedad and Athletic Club. Those institutions have been stitched into the Basque Country's fabric for more than a century. San Mamés and Anoeta, modern as they might be, are cultural cathedrals, emergent icons totally inseparable from the area and its people. I wonder if such a thing can be engineered. Leipzig are certainly going to try.

2025 has not gone smoothly for RB Leipzig. I could not understand a word of the press conferences I attended with Marco Rose in March, but the excellent work of my bilingual colleagues led me to understand he was a man under pressure. Two weeks later, he was gone.

The game with BVB would, in years prior, have been a heavyweight affair, a contest to determine which club would get closest to challenging Bayern Munich's dominance. In March, it was between two flailing outfits punching well below their weight. Dortmund lost 2-0 on the night, but a late-season recovery saw them squeeze into the Champions League places in fourth. RB Leipzig would see no such renewal, and finished 7th.

There has been a similar downturn across the border. Between 2007 and 2023, RB Salzburg won 14 of 17 titles in the Austrian Bundesliga, including a run of ten in a row between 2013 and 2023. In the past two years they've been usurped by striker factory Sturm Graz, and finished last year's regular season in third.

This might be considered the first prolonged plateau in Red Bull's otherwise meteoric European rise. I don't think there's any shared diagnostic to be made between the club's misfortunes: RB Salzburg kept selling their best players, as they were designed to do, and eventually one of many spinning plates fell. For Leipzig, Marco Rose just seemed like the wrong man at the wrong time.

At the time of writing, the club have only just sold Šeško while Simons and Loïs Openda remain, and they've added more talented attackers in SCOUTED favourites Yan Diomandé, Johan Bakayoko and Rǒmulo Cardoso. They are working on a deal to re-sign Christopher Nkunku. Antonio Nusa missed a large part of last season through injury, but is now fit. German international Benjamin Henrichs is closing on a return from a horrific Achilles tear. There will surely be a response to the slump. [Two days before publication, RB Leipzig lost their opening Bundesliga game to Bayern Munich...6-0. - ed]

But if Baum's work is continued by the newly instated Wagner, big international transfers will only be part of Leipzig's recovery strategy.

"We did some research on the best 100 players in the world, where they made their debuts, and in which league," Baum tells me. "And we asked ourselves: so what do those players have in common? And 97% of those players, 97 of 100, made their debut before they left their academy.

"Faik Sakar made his first-team debut this season. In the data, we could see he was very technical but he needs to work more on 'body' [remember the ball, game, body, mind split - ed]. So he gets his own training and game scenes around that. And we have a ‘mirror player’ from the first team: his is Xavi Simons. He uses video from his mirror player to improve."

These 'mirror players' are members of the senior first team that academy players are attached to, and use as models for their development.

"We have eight ‘player profiles’ we use internally," says Baum. "So we say Xavi Simons is this profile, and Faik Sakar is the same. Then we look to the data: here’s Faik’s shot-map, and if you compare it with Xavi Simons, you’ll see Faik has to come more into the box - and when he’s in the box, he has to improve his shooting. That’s one way we compare the players, and from that comes training."

A few weeks after I leave, RB Leipzig host the first iteration of a new tournament at their training complex - an event they call the Wings Cup. PSV and Southampton sent youth teams to participate alongside four Red Bull sides: Leipzig, Salzburg, Bragantino, and New York. You might've seen coverage on Rising Ballers, who were in attendance. Arsène Wenger was, too.

In many ways, the tournament felt like an extension of Baum's comments on youth football being an individual game. The second round was a traditional small-team tournament between the sides; but in the first, players were split up after every game to play with new teammates from other clubs. Players were scored on individual output, not just team performance, and live screens dotted around the training complex blared the player's individual stats live, to provide 'extra motivation'.

Teams, after all, don't make debuts - individuals do.

EPILOGUE: GLASS

On the day RB Leipzig beat Borussia Dortmund 2-0, the afternoon sky is bright and clear. It's chilly in the clean way of early spring. We arrive at the stadium before the fans and walk amongst the quiet, bustling energy of a staff preparing for the deluge of thousands.

Many fans reach the stadium by crossing a glorious green stretch of the Festwiese Leipzig - the city's 'festival meadow'. They arrive in great crowds, enter through ticketing barriers and climb the enormous hill that cradles the Arena. Here they come now, crossing the bridge between the old and new, between stone and steel.

If there was anyone still sitting on the preserved benches of the original Zentralstadion, they'd enjoy a view of nothing but the great shining wall of the RB Arena. If they turned slightly to the left, they'd see thousands of new fans streaming past them, across the bridge and into their sheltered cathedral of glass and steel. Later, they'd hear a muffled roar, as if from far away.

Leipzig was rubble, and now it is something else: a city divided by the political tumult of its country and yet offering an escape from it, an island for those who wish to climb away. Sitting above all the noise, Red Bull GmbH have built a gleaming throne for their project of controlled variables and individualism and mechanical efficiency and relentless, obliterating energy. From this seat they aim to launch a regional footballing empire, and export its produce to the world.

History suggests they'll succeed. The bulls just always run, and they run in a straight line, through all the stone that stands against them.

With thanks to Billy Carpenter and Seb Stafford-Bloor.

Quotes have been edited for clarity and the author’s emphasis has been added.

SCOUTED would like to disclose the author’s trip to Leipzig was conducted as part of a media week hosted by RB Leipzig. Travel and accommodation were paid for by RB Leipzig.