Revenge of the Dribbler

Mazy maestros are back on the menu. Ashwin Raman investigates their return

The dribble is football’s most romanticised action. Goals decide games, but the dribble holds our hearts: from the origins of English football to the South American national sides of the television era to the magic of Lionel Messi, nothing makes us feel like a mesmeric dribbler.

Ashwin Raman is a writer and analyst who, at fifteen years old, was working for Dundee United. Big announcement: this is Ashwin's swan song, his final SCOUTED column before he begins a new life studying in London. Goodbye, sweet prince - and thank you.

Recently, the dribble has become a symbol of both nostalgia and pessimism about the game’s future. “The good dribblers are over, my friend,” wrote Juanma Lillo for The Athletic in 2022. “Where can you find them? I can’t see any.” The Spaniard lamented the supposed homogenisation of the game across all levels, the influence of coaches, and the apparent dominance of “El Dostoquismo” - his phrase for the culture of releasing the ball after just two touches.

Not all of Lillo’s sentiment was misplaced. Early in the 2020s, especially in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and the temporarily-decreased intensity of the game, dribbling was on the decline. To break down defences, many elite sides increasingly used intricate passing and positional rotations rather than eye-catching dribbling.

Random, but most great attacking sides also take on defenders a lot, but two big exceptions this season are City and Inter. And they play each other in the CL final. pic.twitter.com/5l6akgg3Eu

— Ashwin Raman (@AshwinRaman_) May 31, 2023

Then we reach this summer. Eberechi Eze, Luis Diaz, Rayan Cherki, Mohammed Kudus, Xavi Simons, Noni Madueke, Jamie Gittens, Tijjani Reijnders, Ardon Jashari, Alex Baena, Eliesse Ben Seghir, Bilal El Khannouss; dribblers and carriers of all kinds were coveted. And that’s not counting those at the centre of the rumour mill who didn’t get moves: Savinho, Magnes Akliouche, Carlos Baleba, Nico Paz, and many more.

Pep Guardiola, often painted as the primary antagonist of the dribble, began to rely on the electric dribbling of Jeremy Doku and Savinho to break down blocks last season. Now he is integrating players like Cherki, Reijnders, and breakout-star-in-waiting Oscar Bobb.

Something’s shifted. But what? Is it coincidence? Divine intervention? Or has something changed tactically, influencing the kinds of skillsets teams value now?

The good dribblers are here, my friend. Let’s see what the stats tell us.

Statistical trends

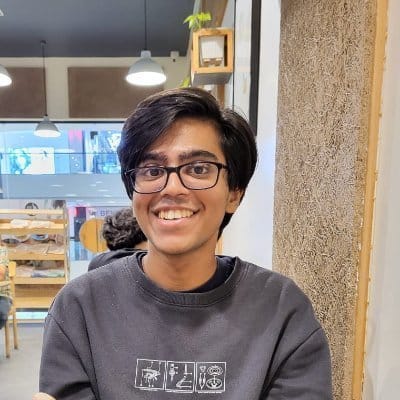

We’ll begin with a fact that may sound at odds with the topic of the piece: the number of dribbles attempted by each team isn’t increasing with every passing year. In fact, the 2022-23 season, when Lillo wrote his column and City and Inter reached the Champions League final, saw the most dribbles attempted in the Big Five Leagues since 2017.

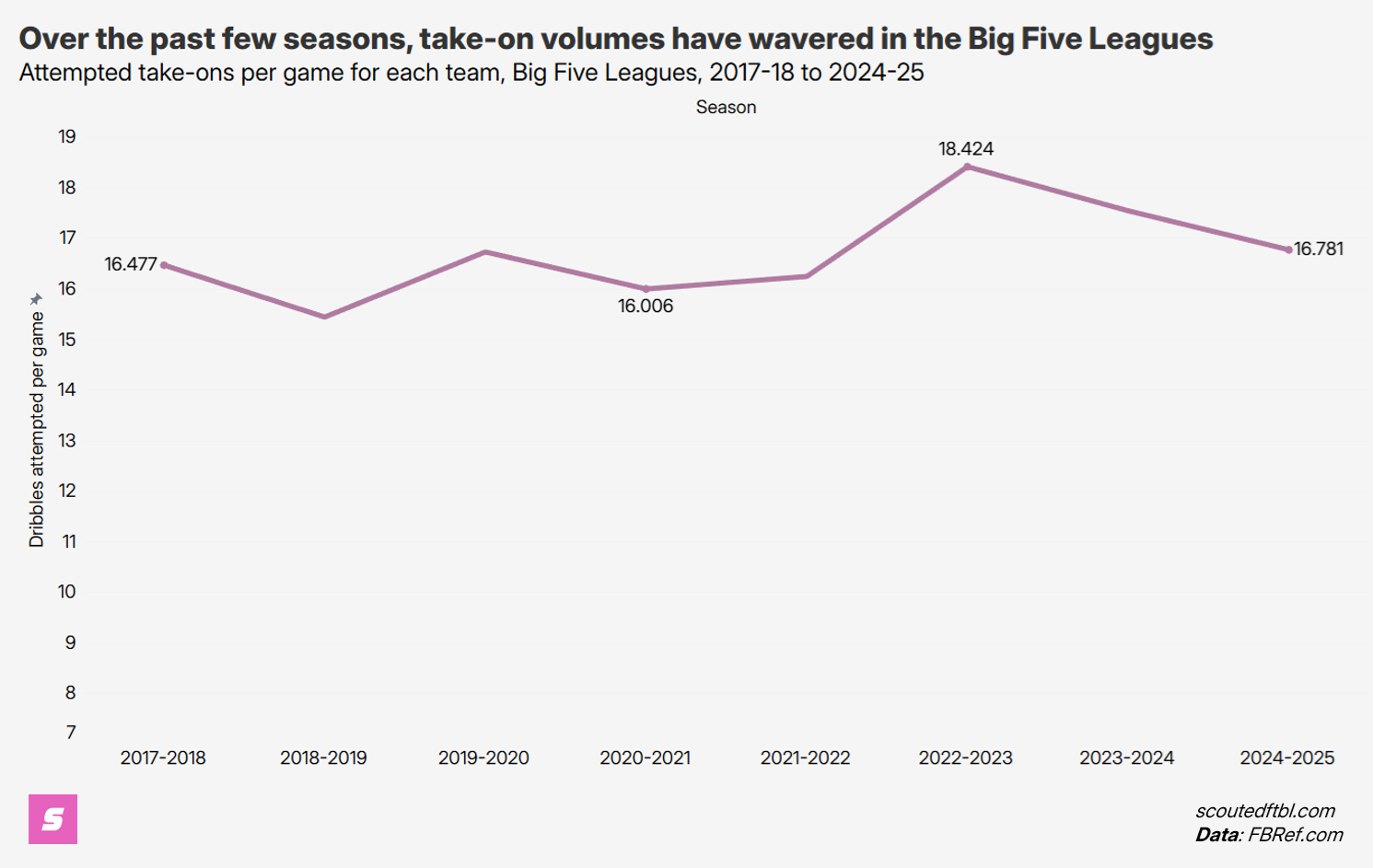

Looking at ball progression gives us a more clear trend. Since 2020, teams have increasingly been relying on ball-carrying to get the ball into the box. These percentage increases may seem small, but they translate to major changes on the pitch: the average game in 2025 sees around 16 more carries into the box than a game in 2020.

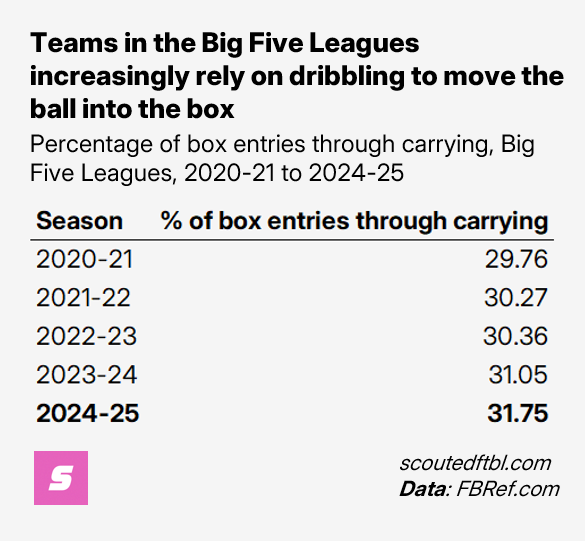

Plus, since 2022, passes have been becoming slightly shorter, while carries have become slightly longer. The average carry moves the ball forward a little more than in the 2022-23 season.

As a result, while take-ons haven’t definitively become more common, teams are clearly using dribbling to turn possession into threatening situations in the box. On the whole, the return of the dribble seems a trend that’s developing rather than a full-fledged paradigm shift that’s already in effect. Let’s take a look at what’s behind this trend.

- Man-marking and duels

As Jon Mackenzie told us last month, one of the defining tactical trends of the past half-decade is the proliferation of man-marking. Whether teams go man-for-man all the time or start in a settled block and make the switch situationally (known as a ‘hybrid press’), giving every player out of possession a set man-marking duty has increasingly become the default for most high-level sides, from mid-table to title winners. What’s more, recent months have seen teams take their man-marking to new levels, from City’s (unsuccessful) experiment in going man-for-man all the way to the opposition goalkeeper…

This is the set up vs goal kick. Here's the thing. City are going m2m with their front 5 players. Nothing odd there on paper until you realise they're going m2m against the GOALKEEPER as well. So it's CF->GK, WFs->CBs, CMs->CMs... pic.twitter.com/0hE0OgZDFQ

— Jon Mackenzie (@Jon_Mackenzie) September 2, 2025

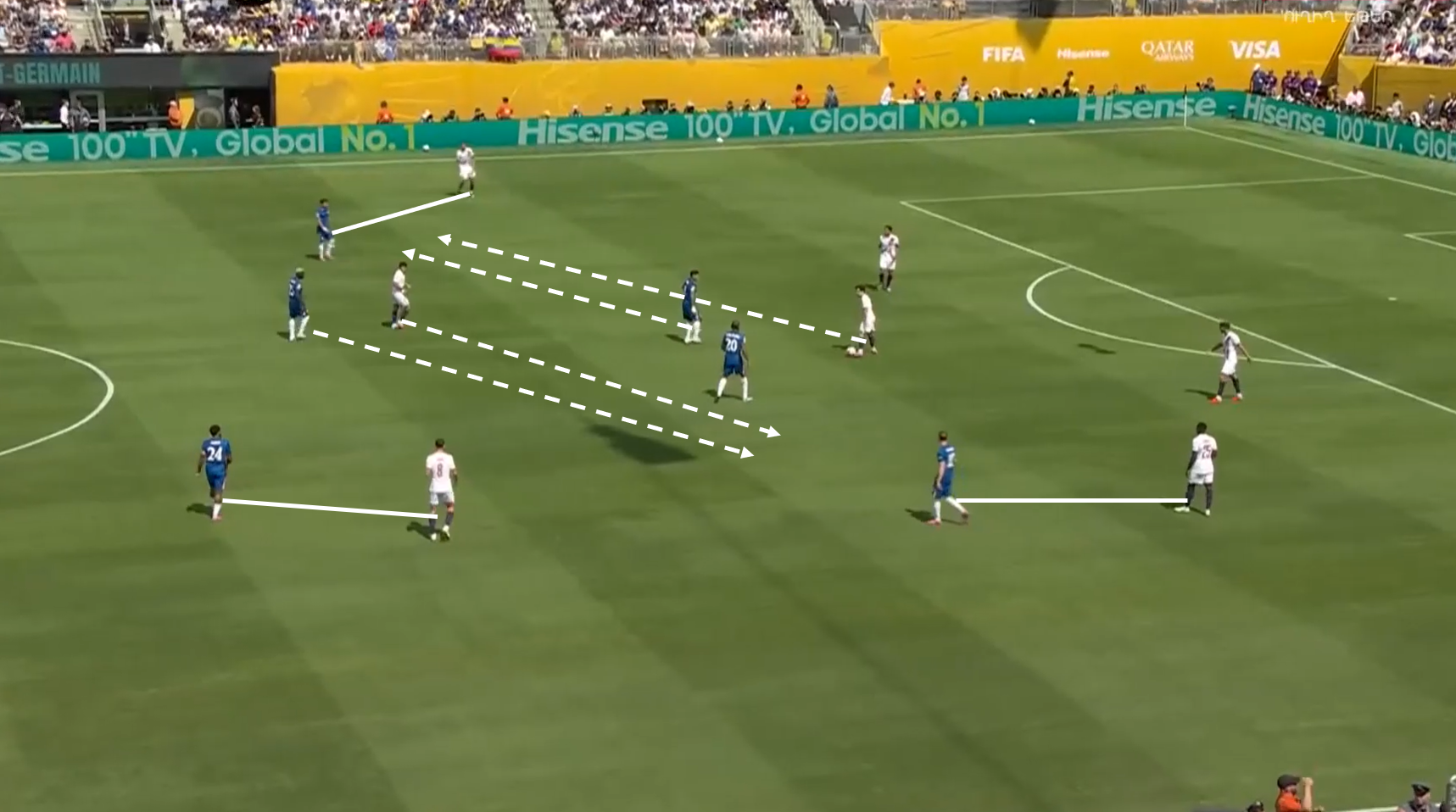

…to teams like Bayern and Chelsea blunting the effect of PSG’s positional rotations by simply never switching marking duties between players, with markers following their assignments no matter what, as Victor Lefaucheux writes.

More intense man-marking schemes necessitate new ways of breaking them down in possession. As Judah Davies writes for Spielverlagerung, man-marking “seeks to pitch the game into a series of 1v1 duels”, based on individual defensive responsibilities. “As such,” he continues, “being able to get free from an opponent on an individual level can be the basis to unbalance the opponent’s whole structure.” One straightforward way of dislodging man-marking systems on an individual level is to beat markers on the dribble.

Of course, dribbling past a marker opens up space ahead for the ball-carrier to exploit, especially if the attacking team is well spaced-out, but another advantage of dribbling against man-marking systems is that it attracts defenders towards the ball, putting man-marking responsibilities in disarray. In other words, dribbling gravity is especially useful when defences go man-for-man.

For instance, look at Eze pulling two extra defenders towards him and unsettling Fulham’s marking assignments, turning multiple one-on-ones across the pitch into a three-on-one against him, which he still wins.

Therefore, banking on dribbling skill is a surefire way of manipulating and breaking down the intense man-marking systems that we see today, and it wouldn’t be surprising to see more teams adding players known for their ball control in tight spaces to respond to the way teams defend now.

- Narrow mid-blocks and attacking ‘around’ them

Changes in pressing and marking gambits have been defining features of football in the 2020s. High pressing has cooled off a bit in the top leagues since the late 2010s, even long after the decreased intensity levels of COVID-ball. While teams allowed only 11.2 passes per defensive action (PPDA) in their opponent’s half in the 2021-22 season, they allowed 12 PPDA in the opposition’s half last season. Sure, the decimal differences may not appear to be huge swings, but they represent a changing situation on the pitch. Teams increasingly deploy player-oriented mid-blocks, emphasising packing the middle.

This naturally changes the way teams attack. As Liam Tharne writes for The Athletic, the through ball has been in perennial decline since the late 2010s. Rather than attacking ‘through’ defences, teams now have to find ways to attack ‘around’ them. As a result, a lot more of middle-third passing today tends to be diagonal or lateral, moving the ball towards the flanks.

Teams have devised several ways to approach defences that look to cancel out central midfield. They can ‘empty out’ central spaces in possession or move their build-up play through the flanks, and the ball-dominant playmakers of many teams last season, like City’s Kevin de Bruyne, Arsenal’s Martin Ødegaard, or even Leicester’s Bilal El Khannouss, would move out wide to receive the ball and pull defences out of shape.

As any expected passing model would tell you, it’s harder to complete passes from the flanks towards central areas. This is because the touchline, the best defender in the world, cuts off the passing angles available to the player with the ball. Consequently, dribbling ahead into dangerous areas becomes a worthwhile alternative. When high-possession sides run into settled blocks these days, letting a talented dribbler ‘cook’ out wide turns into an easy way of getting the ball closer to the box.

Moreover, ball progression isn’t the only advantage that dribbling out wide presents. A winger’s dribbling gravity can lure defenders out wide and create space in central areas, making life much easier against a packed defence.

Consequently, taking defenders on is yet another way for attacking teams to respond to changing defensive dynamics, making dribble-y wingers an even more prized commodity.

- Transitions and ball-carrying

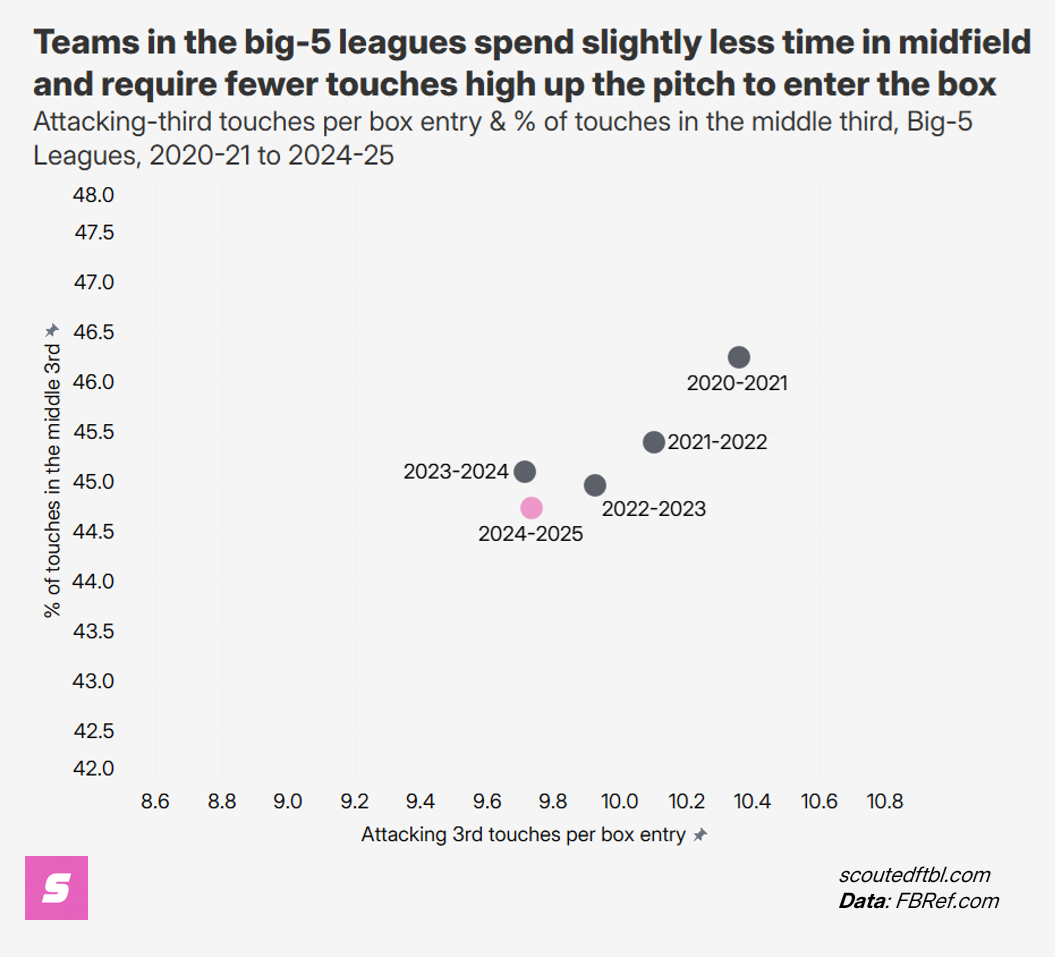

With changes in pressing and teams attacking more directly, moving from one end of the pitch to the other more quickly, the transition game continues to rise in prominence. As Alex Barker noted, elite sides take far fewer of their touches in the middle third of the pitch now. Plus, when teams get into the attacking third, they move the ball around far less before being able to enter the box.

Additionally, Billy Carpenter points out that no league has seen as drastic a depopulation of the middle third as the Premier League, followed by the next highest-spending European league, Serie A. Clearly, the top level of the game trends towards being more direct, bypassing the midfield, and playing on the transition.

Last season, Premier League teams had the lowest share of touches in the middle third across Europe's top five leagues.

— Billy Carpenter (@billycarpy) July 29, 2025

The average Premier League team had 29.1 fewer middle-third touches per match than in 2020/21. pic.twitter.com/NFBqPEDLWd

As you’d expect, a more direct, transition-based game also means more ball-carrying responsibilities. Whether it’s through the centre with runners on the flanks or surging up the wings, transition situations tend to involve players carrying the ball a long distance up the pitch. This helps explain why the average carry moves the ball forward more now.

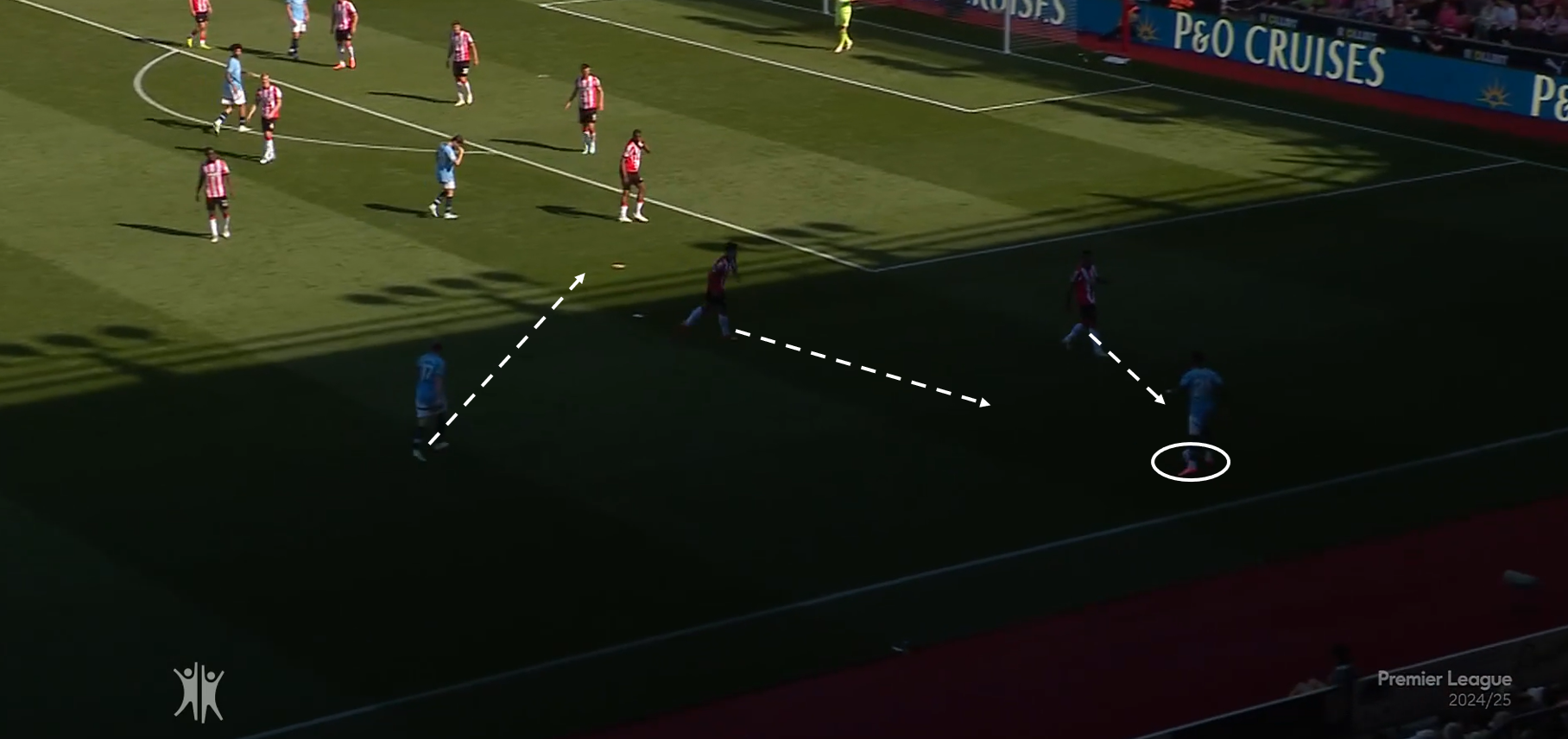

Plus, among teams who bait the press and create ‘artificial transitions’, like Roberto de Zerbi’s teams or Fabian Hürzeler’s Brighton, ball-carriers in midfield can help swiftly break lines and change the tempo of a passing move. A series of quick one-touch passing is often followed by a player receiving on the turn and carrying the ball out of pressure, as Baleba often does for Brighton.

Run, Carlos, run! 😅🏃 The best of Baleba's trademark driving runs during his first season! 🔥 pic.twitter.com/CjOYEfnN4h

— Brighton & Hove Albion (@OfficialBHAFC) June 4, 2024

All in all, dribbling skill becomes increasingly valuable in every facet of in-possession play because of the way football tactics have changed over the past few years. It’s no surprise that most of the creative players linked to big-money moves last season are primarily known for their dribbling rather than their ball progression or their final ball, and we might just see this trend continue to play out in the next couple of transfer windows.

For all the prominence attached to the dribble, the footballing world seems under-equipped to truly understand it. Despite a few ingenious approaches like Euan Dewar’s dribbling metrics, on-ball event data can’t fully capture what a dribble does to a defence. ‘Take-ons completed per 90’ figures are reductive, ball progression stats don’t represent space manipulation, and post-dribble shot-creation stats tend to measure team context or what happens after the dribble, rather than the dribble itself. Emerging developments in player tracking data will be the next frontier, shining a light on space and player positioning.

The traditional ‘eye-test’ and the established vocabulary of the game aren’t a whole lot fancier at the moment, either. The word ‘gravity’, to describe players being pulled towards the dribbler hasn’t made many inroads into football’s dictionary from basketball analysis, where it’s used to describe how great shooters pull defences out of shape. Plus, the romanticisation of the dribble tends to obscure its value on the pitch. Rather than just presenting aesthetic value and fodder for ‘<Player X> Top 100 Skills’ compilations, dribbling carries functional advantages and helps unsettle defences and get the ball up the pitch.

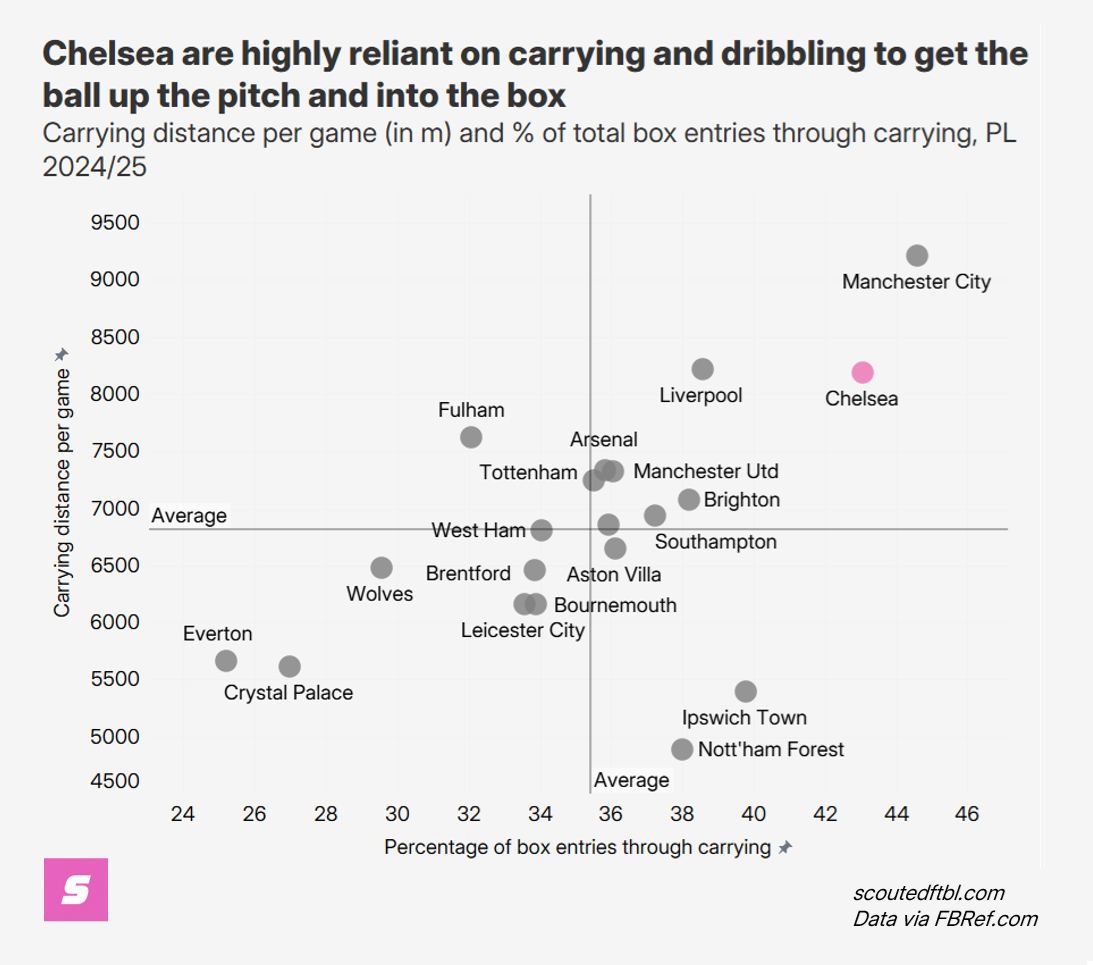

Moreover, while the bogeyman of Guardiola-esque ‘positional play’ is often described as being antithetical to high-volume dribbling, all of Guardiola’s sides have used dribbling as a tool, from Lionel Messi and Andres Iniesta’s mazy dribbles at his Barcelona to wingers like Riyad Mahrez and Jeremy Doku being isolated on one flank to manipulate defences and get the ball into the box. With the setups that defences have converged towards in the 2020s, it’s unsurprising that Guardiola’s City uses dribbling now more than ever. What’s more, another big side that relies on dribbling to move into dangerous areas is Enzo Maresca’s Chelsea, a side that displays some of the most textbook positional-play-based attacking, with players spread across vertical spaces ‘rationally’.

A player who can beat others with the ball at their feet or carry the ball swiftly into space is more valuable now than at the beginning of the 2020s because tactical dynamics have shifted. This changed the last transfer window, and it’ll probably influence the next few, too.

It appears reports of the dribbler’s demise have been greatly exaggerated.