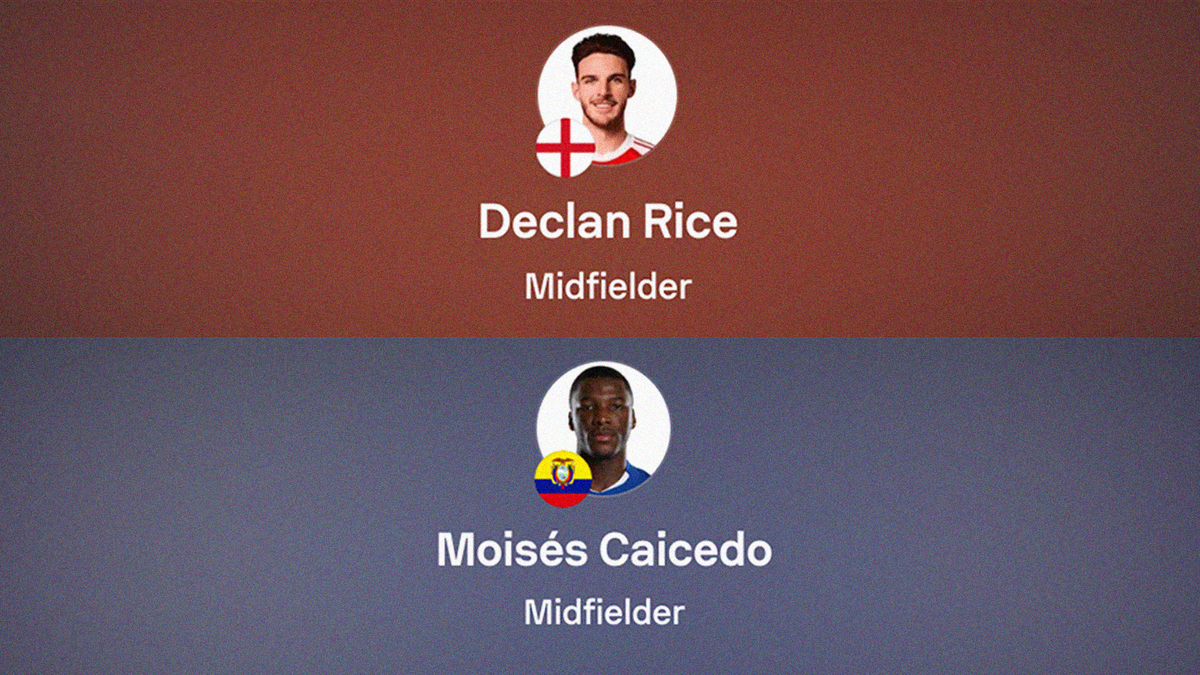

Declan Rice v Moisés Caicedo

Monday Night SCOUTED presents: a crab and a horse fight to the death

Mohamed Salah versus Eden Hazard. Virgil van Dijk versus Nemanja Vidić. Moisés Caicedo versus Declan Rice. Not a single international break passes by without at least one of these debates flooding social media timelines.

This time, I have successfully resisted the urge to engage...on the timeline.

Instead I've written 2000 words on the issue. I hope, through this newsletter, to highlight the foolishness of this debate by viewing it through the lens of totally non-foolish and sensible animal-inspired metrics. Forgive me, for I am about to engage in discourse: not to provide a definitive answer, but to demonstrate how dumb the debate is in the first place. Maybe everyone will read this and log off for a bit? Of course not. But it won’t stop me from trying.

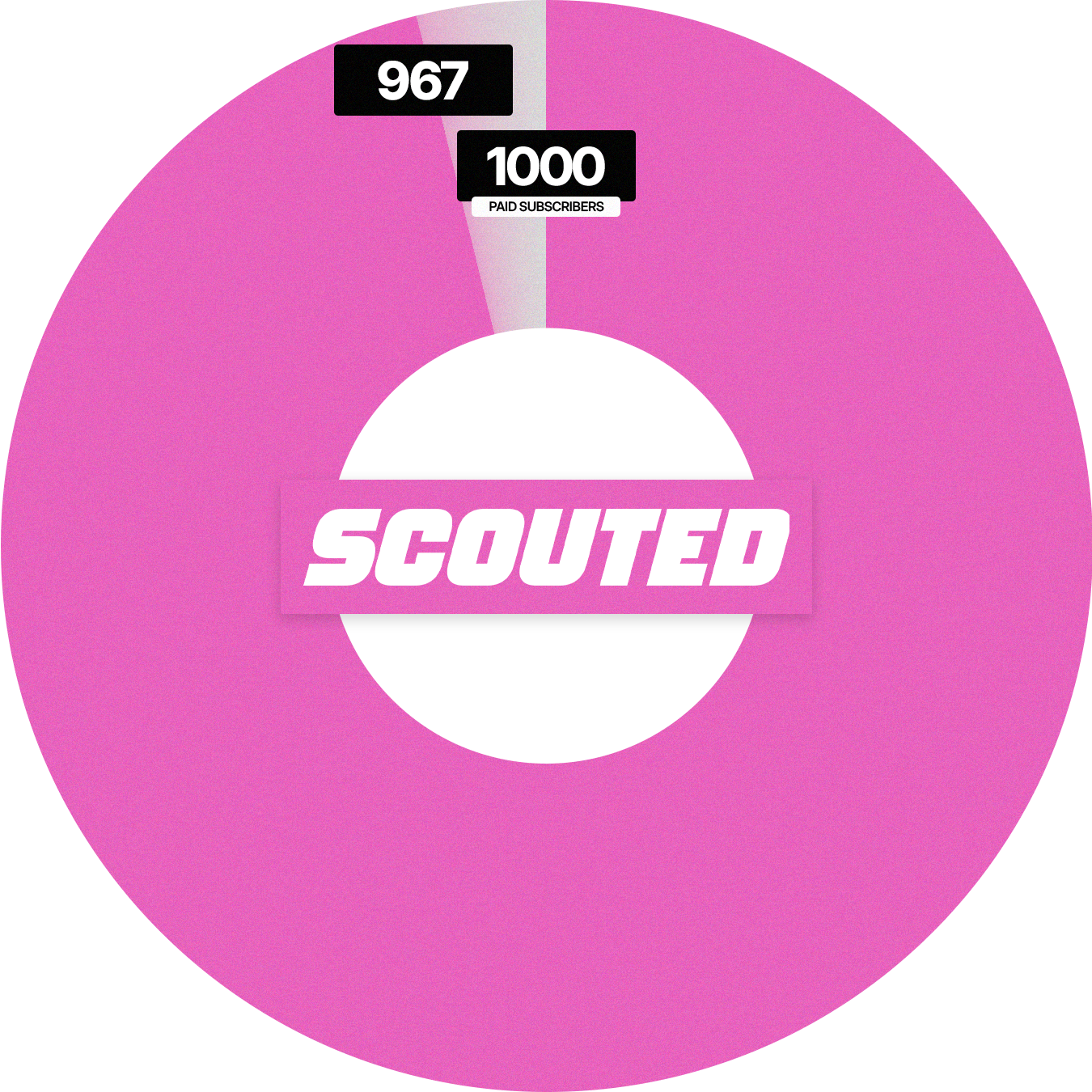

967/1000 subs

We're so close.

Help us reach another milestone towards our dream of sustainable, independent football writing.